Don’t Watch That, Watch This by Mark Peckett

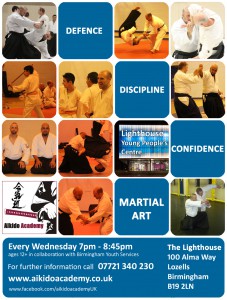

It’s always nice to see kids’ aikido classes. Lots of smiles and lots of fun; but my experience is that not many juniors go on to study aikido as adults. Why is that? First and foremost, it’s not a reflection on the teachers; I have seen many excellent teachers of children and classes full of fun and learning. And it’s also not a reflection on the students themselves; it’s not that they aren’t keen or don’t practise hard enough.

It’s always nice to see kids’ aikido classes. Lots of smiles and lots of fun; but my experience is that not many juniors go on to study aikido as adults. Why is that? First and foremost, it’s not a reflection on the teachers; I have seen many excellent teachers of children and classes full of fun and learning. And it’s also not a reflection on the students themselves; it’s not that they aren’t keen or don’t practise hard enough.

Obviously in your teens some things become very important: being part of the crowd, the opposite sex, and doing all the things your parents don’t approve of, but I don’t think these are necessarily the things that stop younger people doing aikido.

Conversely, I believe it is the one thing which has kept me interested in aikido over the years: that nothing is what it seems.

Let me explain: I attended a seminar recently where one of the instructors spoke of allowing uke to fall. We were practising irimi nage: entering throw. Over the years I’ve heard many sensei caution about being in a hurry to “get to the throw”, but this was the first time I had heard the throw being described as a point where uke has no option but to choose to fall.

This is what I mean about nothing being what it seems. That hour with sensei Alan Morton of Ocean State Aikido made me revise my thinking about aikido –again! I find that over the years much of my practice has been like this. It is a series of Copernican revolutions. When Copernicus said the Earth went round the Sun and not the other way round, nothing in the world changed, and at the same time it was a major shift in the worldview. So I still go to practice, I still do the same techniques, but now I do them with a different feeling and for a different reason.

This is the reason why I think adults usually stick with aikido and children tend not to. You need to be older and wiser, to have more life experience to appreciate how small changes can make such a big difference.

In teaching I have often likened aikido to a stage magician performing magic. By subtle misdirection the magician causes you to look in the wrong place while he is doing something-or-other in the right place; you watch his right hand waving in the air whilst at the same time he is slipping a dove unnoticed from his pocket.

Now I am not saying that aikido is about trickery – although there are unscrupulous teachers out there who use this misdirection to their advantage, dressing up technique with the mysteries of ki rather than teaching good basics such as proper posture, timing and extension – but I am saying that aikido can fool us without the aid of a magician.

Or to put it another way: sankyo can be a hard technique for beginners to grasp – no pun intended! This is for a number of reasons not least of which is that it is hard to appreciate that in order to make uke rise it is not necessary for tori to rise too; in fact, exactly the opposite. But even when you get past these basic principles, you will hear people complaining that they “can’t get it to work”.

This is because their focus tends to be on the wrist, where the technique is apparently being applied. In fact, the torsion of sankyo runs all the way up to the arm through the elbow into the shoulder, and brings uke to a position in which he can no longer move either his elbow or shoulder. When I can’t get a technique to work, my first question to myself is: “Where is my attention? Is it in the wrong place?” And I find that very often I have been focussing too closely on what my hands were doing instead of what is or isn’t happening to uke’s body, or where my body is in relation to uke’s; in fact a whole world outside of my narrow focus.

Aikido is a long study. It is only half-jokingly that irimi-nage or entering throw is called “the thirty year technique.” Ikkyo is regarded as the simplest of the immobilisations and actually means, in one translation, “first basic technique.” Because of this it often the first technique taught to beginners; and yet I have always regarded it as one of the hardest to do well.

But I realise now, thirty years too late, that the reason it is taught first is because it contains so many of the principles I mentioned earlier. GozoShioda says of the finish to ikkyo:

“Beginners find it difficult to apply pressure directly downwards from a seiza[sitting] position, but it is only through techniques such as this that the true power of aikido, i.e. using the focused power of the whole body, can be learned … it could be said that ikkajo [ikkyo] is the most basic of techniques and also the most difficult.”

There are three particular principles in Judo: kuzushi, or unbalancing the opponent; tsukuri, or the correct action for the attack; and kake, the attack itself. It is very easy in aikido to see the attack, and since most practice is predetermined, one is very well aware of the correct action, but often the initial unbalancing is completely missed. Perhaps there is an atemi, or strike, which has not been noticed. Morihiro Saito says:

“Atemi are an essential part of basic and advanced techniques and should not be omitted from your practice.”

There is always something new to learn, or to be taught. And this is what continues to thrill me and brings me back to aikido, and I suspect it applies to most other aikido practitioners too. And all of those lessons are also lessons to be applied outside the dojo.

We can always try to extend our attention outside of our narrow focus.